Online behemoths like Amazon may be cheaper, but can anything beat a real shop run by a book-lover? As indie bookshops grow in number for the second year after a 20-year decline, we meet some of the people tempting us back to the high street

Rising in defiance of faceless online mega-retailers and woeful high street sales, new independent booksellers are setting up shop across Britain. In the 20 years after 1995 the numbers of bookshops plummeted, followed in 2016 by their ranks increasing by just one. Having lost more than 1,000 bookshops in the UK, this apparent turnaround was intriguing. Then, in 2018, a total of 12 bookshops opened their doors for the first time.

One of these is Max Minerva’s Marvellous Books, in north Bristol. In the summer of 2018, Sam Taylor came across a note in the window of an empty shop, asking locals what they would like to see in the space.

On a whim, Taylor found an envelope, jotted down that he would open a bookshop, and slipped it through the door. He received a call soon after. He and his wife Jessica Paul (pictured above) drew up a business plan, gave up their jobs, and opened in September 2018. “The community really supported the bookshop that was here before for 20 years, so we knew that it could work,” says Paul.

“Having had a bookshop here and lost it, locals really know its importance and what it brings to the high street.”

By running schemes such as creative writing classes for children, the shop involves residents of all ages. Paul even phones up her regular customers when new stock arrives. One is a “lovely history buff”, who curiously “only purchases books on the King Richards, no one else”.

But why, given that prices are often slightly cheaper online, are people turning back to independents? “There’s been a lot of recent publicity about how Amazon – for example – treats its staff,” says Emily Ross, another Bristol-based bookseller. “I think it makes people stop and think: ‘actually I’m going to support my local shop’, and this uplifts the community as a whole.”

Soon after quitting her job in publishing, Ross and her husband Dan moved to Bristol to open Storysmith, in Bedminster, to the south of the city. “We can do so much more than Amazon can,” she enthuses. “We chat to everybody that comes in, and they suggest books to us too; it’s a two-way process.”

Emily Ross, who runs Storysmith in Bristol with her husband Dan (and shop dog, Roy)

Like many other emerging bookshops, Storysmith differentiates itself through hosting events such as its Mothership Writers programme: a free, year-long series of writing workshops for new mums. By focusing on becoming community hubs – think well-thought-out spaces and room for discussions – establishments like Storysmith are finding success and galvanising support.

“We want people to know that bookshops aren’t highbrow places to visit,” says Ross.

The threat of online retailers and e-readers lingers, of course, but some booksellers do not necessarily consider them direct competition.

The first Kindle was released in 2007, selling out in five and a half hours. This was followed by widespread doom-mongering about the demise of physical books.

We chat to everybody that comes in, and they suggest books to us too; it’s a two-way process

But it is sales of e-readers and e-books that have slowed, the latter dropping by 17 per cent in 2016 alone. It could be ‘screen fatigue’, some have suggested, people deciding that they already spend long enough staring at screens.

By contrast, there was a 31 per cent increase in the sales of hardback books in 2017. “There’s just no comparison to holding and smelling a book. Books are collectable things – to have and keep,” smiles Ross.

Storysmith hosts regular events. Its owners want to nurture a community hub, as well as a shop

Over at Phlox Books, which opened in east London two years ago, its owner, Belfast-born bibliophile Aimée Madill, agrees: “You cannot replace the physicality of a book.” Armed with a startup loan, 10 years’ experience of working in bookshops and an absolute passion for the written word, Madill wanted to create a “lived-in” space that reminded customers of a time “when the local bookshop was the heart of your community”. Rather than packing in as many titles as possible to drive profits, she arranges them with care.

With the cheerful motto ‘books, booze and coffee’, she tries to “de-rarify” literature for her visitors, including parents who want to simply sit and have a drink, while their kids leaf through the books. As its maxim suggests, Phlox Books has an alcohol licence. Madill wants to create an ‘experience’, as well as supplying quality literature.

She credits the shop’s success to her “unbelievable” repeat customers, and also to a curation of books that understands its customer base. “Our selection reacts to what’s happening in the news and arts: it isn’t just based on an algorithm of what you bought before.”

Our selection reacts to what’s happening in the news and arts: it isn’t just based on an algorithm of what you bought before

In common with other new bookshops, Phlox offers a subscription service through which subscribers regularly receive a carefully chosen tome in the post. To personalise this, Madill invites local subscribers for an initial coffee and a chat in the shop. “I ask if there’s a topic they haven’t yet felt they could approach. Or, is there a pressure point in their life that we can provide some release for through literature?”

Books for human beings

Is it this kind of meaningful exchange, devoid of machines, that draws us back to bookshops?

“People are really starting to value the time that they spend with someone on the retail floor,” Madill thinks. Social media has been an ally too. “It enables us to tell a story. For example, that since we’ve opened, we’ve acquired two babies and a dog! People are able to follow the shop’s journey, and to see that there’s a family behind it.”

Madill has acquired two children and a dog since opening Phlox Books

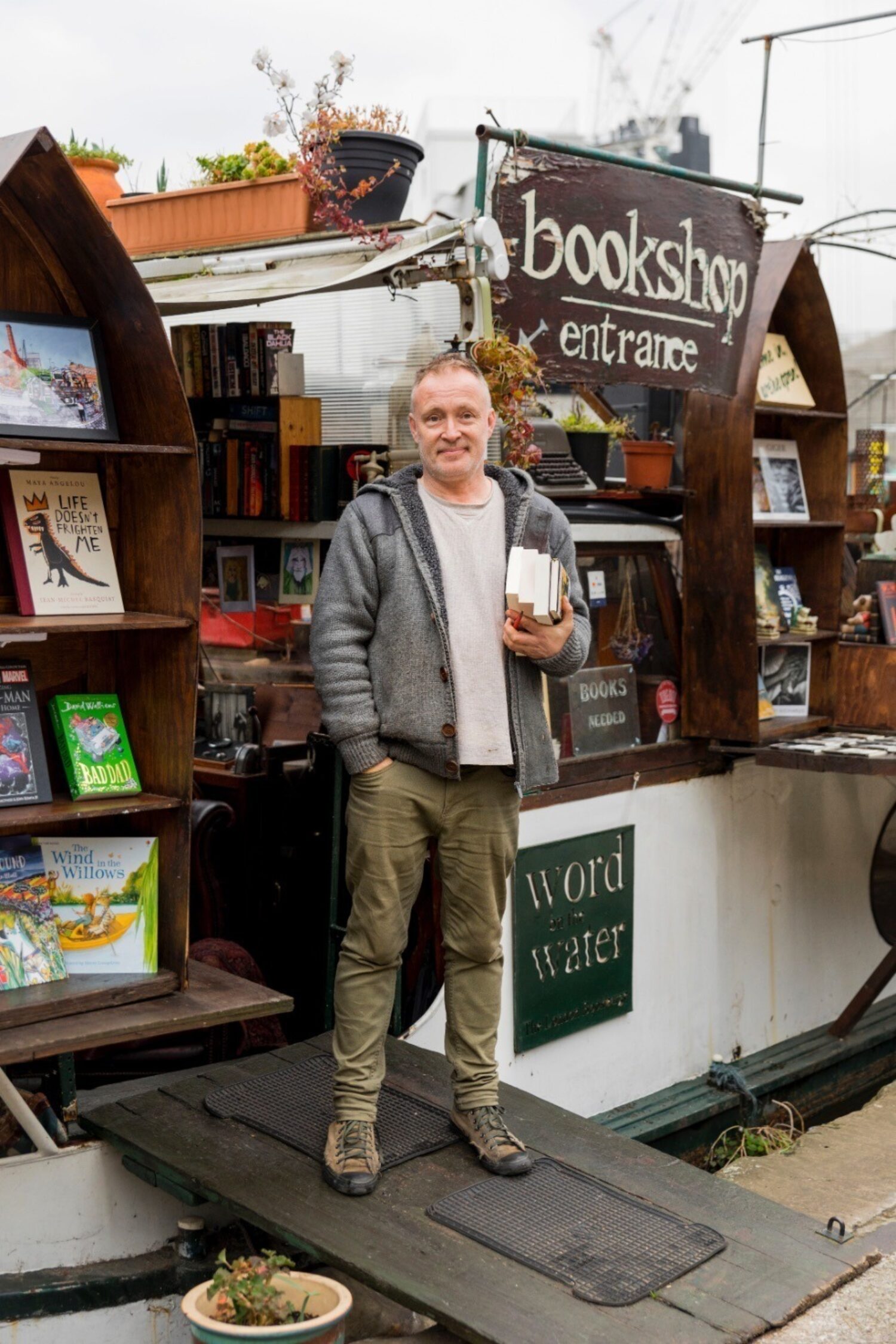

Were it not for social media, London’s only floating bookshop – Word on the Water – would no longer exist. After six arduous years of having to change the location of the 1920s Dutch barge every fortnight to comply with regulations, the three owners decided to squat by Paddington, until ordered to move.

They posted online the threatening letters they received, which were seen by more than a million people in one day, resulting in huge pressure being put on the Canal & River Trust: the body that oversees the licensing of boats on British waterways.

‘The London Bookbarge’ was eventually offered a permanent spot in King’s Cross. Here, it hosts open mic sessions and a popular monthly jazz and poetry event, which attracts up to 1,000 attendees.

“Local bookshops are almost like secular churches in Britain nowadays,” suggests co-owner Paddy Screech. “They’re old things that people liked and trusted, and this has value, possibly because of the speed of change. A lot of new things have turned out to be untrustworthy.”

‘Indie bookshops are like a healing balm for modern living,’ says Screech

National campaigns such as Books Are My Bag by the Booksellers Association (BA) have helped to “change the persistent media narrative that books and bookshops are doomed”, as Tim Godfray of the organisation put it.

With the public’s support, 2019 may see more innovative booksellers enter the scene. But pressures remain: online competition and high business rates, to name but two. “We ask the government to take the steps needed to protect the future of bookshops and their high streets,” says Meryl Halls, BA chief executive. That said, a BA survey found that 63.5 per cent of booksellers reported that customer numbers rose for Christmas 2018 compared with 2017.

“Indie bookshops are like a healing balm for modern living,” sums up Screech from Word on the Water. “We’re giving humans what humans want, rather than what corporations think humans will make do with.”

Read more: Back to basics: five old-school pleasures that are enjoying a revival