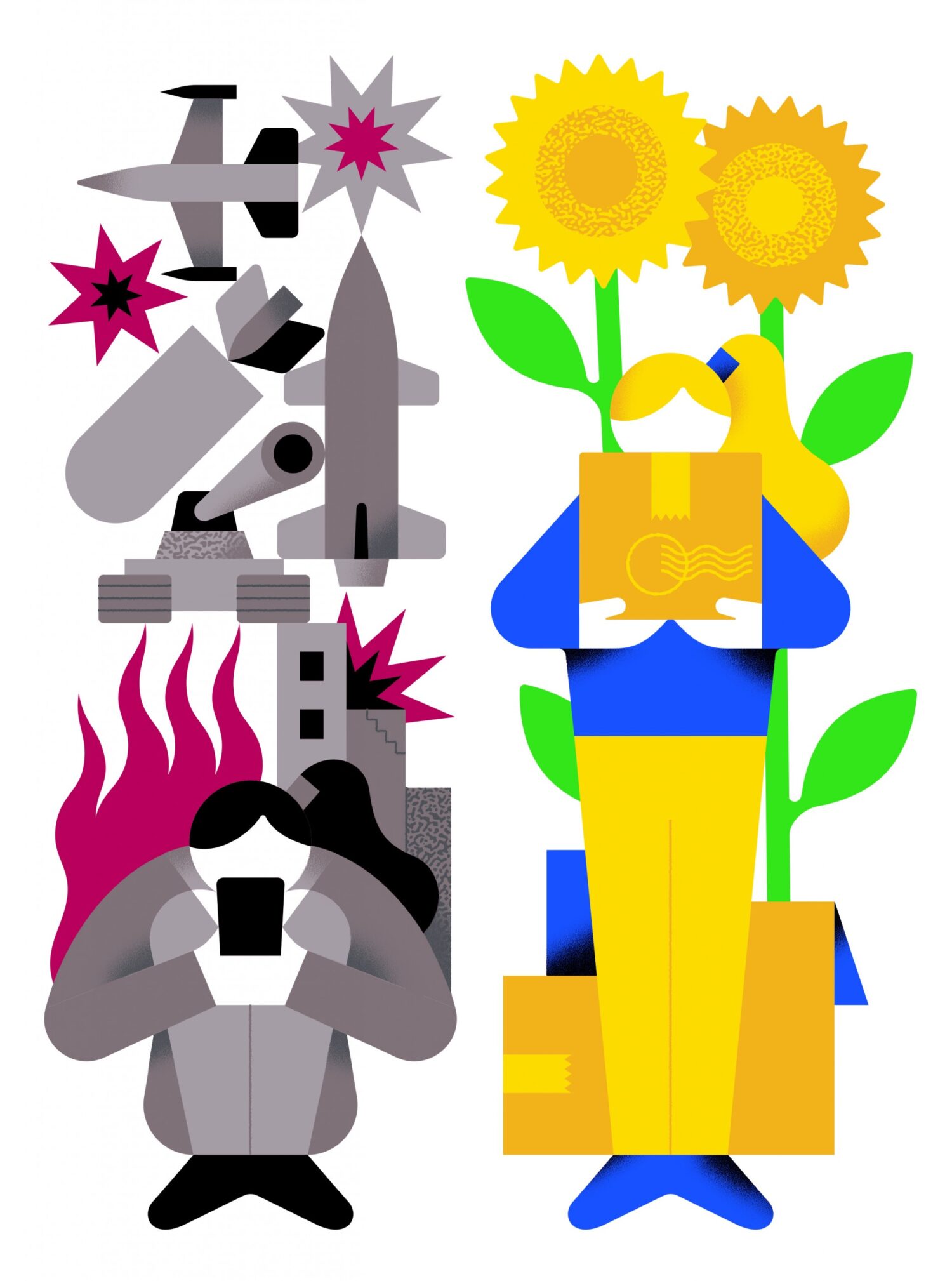

Submerging yourself 24/7 in dreadful news doesn’t help anyone, not least Ukrainian refugees, writes Oliver Burkeman. Put boundaries on the news and focus instead on the concrete actions you can take

History, apparently, doesn’t believe in pacing itself these days. No sooner had it seemed as though Covid was finally beginning to slip into the past than Vladimir Putin began his invasion of Ukraine, killing thousands, displacing millions, and threatening the entire planet with his terrifying nuclear rhetoric.

I’ve no idea how any of this will unfold, of course. But there’s one prediction I feel confident in making: whatever happens, the news cycle isn’t about to become less panic-inducing, less filled with existential threat. Which means that figuring out how to consume news sanely is only going to become an even more critical skill for living a composed and purposeful life.

Alarming news is nothing new, but the central place the news has come to occupy in many people’s psychological worlds is certainly novel. Because of how digital media works – though also because the news developments themselves are legitimately huge – these global dramas start to feel like life’s centre of gravity, with the immediate worlds of family, job and neighbourhood relegated to the periphery.

People sometimes misinterpret the point, so just to be clear: the global dramas obviously affect our daily lives – acutely and horrifyingly, if you’re in Kyiv today, but even if you live in Leeds or Louisville. And how we live our daily lives has an impact in the opposite direction, too, climate change being only the most prominent example.

But assuming you’re not reading this in an active war zone, it doesn’t follow that you need to mentally inhabit those stories, all day long. It doesn’t make you a better person – and it doesn’t make life any easier for Ukrainian refugees – to spend hour upon hour marinating in precisely those narratives over which you can exert the least influence.

In short: I think it really is OK to shift your centre of psychological gravity back from the news cycle to the world around you. The question is … how?

Stop reading the news?

One response, popular in self-development circles, is renunciation: just stop reading the news. But apart from being ethically dubious (is it really OK to check out entirely, just because a given crisis hasn’t reached your doorstep yet?), I’ve found that this doesn’t work in practice as an antidote to anxiety.

Unless you’re also going to renounce all contact with people who do follow the news, you’re inevitably going to pick up on major developments. And then you’ll probably end up with the additional worry that your self-imposed isolation means you’ll be the last to hear that World War Three has begun.

The opposite tactic is what you might call the ‘self-care approach’, typified by those articles offering lists of ways to be kind to yourself when the news is freaking you out. But these make an assumption I’m unwilling to buy into: that it’s inevitable that we’ll spend large chunks of time wallowing in despair about world events, and that the best we can hope for is to remember to treat ourselves to hot baths and walks in the park.

I think there’s a third option: adjusting your default state, so that the news once again becomes something you dip into for a short while, then out of again – as opposed to a realm in which you spend most of your day. And of course, when it comes to the news that you do choose to consume, balancing stories about what’s going wrong, with those focused on what’s going right, can help you to feel empowered.

Putting news back in its box

The blogger David Cain has written eloquently of his longing to put the internet “back in a box in the basement”. This, I’d say, should be our aspiration with the news as well: to check in on it a couple of times a day. To take any relevant concrete actions you can, such as donating to Ukraine. And then to step away and move on.

It doesn’t make you a better person to spend hours marinating in the narratives over which you can exert the least influence

Formulating a handful of not-too-rigid personal rules can make a big difference here. For example, I’ve had success with leaving my phone in the hallway when I’m home; only checking Twitter during a predetermined two-hour period each day; and deciding in advance how I’ll spend work breaks, so I don’t just slide back into news-checking. Such tactics don’t make it effortless to avoid doomscrolling. But they do provide enough of a framework that at any given moment I’m either following them, or conscious of the fact that I’m failing to do so.

It’s been common in recent weeks to see people complaining that it’s hard to get any work done, or to get on with ordinary life in general. But perhaps you just need to get on with things. If you wait, instead, for all the existential threats to pass, all the desperate human suffering to subside, you’ll be waiting forever.

So don’t wait. Not just because marinating in the news helps no-one, but because what you’ll be doing instead – meaningful work, keeping your community functioning, being a good-enough parent or a decent friend – that actively does help. There’s something you’re here to do. And I highly doubt that it’s doomscrolling.

Oliver Burkeman is the author of The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Can’t Stand Positive Thinking, and of Help! How to Become Slightly Happier and Get a Bit More Done. His latest book, Four Thousand Weeks, is about embracing your limitations, and finally getting round to what counts. Twice monthly he publishes The Imperfectionist, an email about building a meaningful life in an age of bewilderment, from which this article is adapted

Main illustration: Bakal

Illustration: Andrea Manzati